How to Quickly Learn Your Way Around A New Place

I’m naturally pretty average at navigation. I’m not bad – at least since my teens, I’ve always been able to use a map (GPS-enabled or not) or listen to directions and get myself to the right place, maybe after a few wrong turns and a little bit of frustration. But I would never have claimed to be good at it or written a blog post about it until recently. Then, over the last couple of years, I decided I’d like to change that. I engaged in some deliberate practice and applied a bunch of techniques, and I’ve gotten noticeably better.

I moved to Minneapolis in the last week of November, having only minimal previous experience with the city, so this makes a great test. And I think I’m doing pretty well: a little less than two months later, I obviously still have to look at a map pretty frequently to find new places I haven’t been to yet, but I haven’t used turn-by-turn directions to get around the city since mid-December; I have never gotten lost in the sense that I didn’t know what part of the city I was in or what direction home was; and in the neighborhoods I spend the most time in, I already know most of the street names and routes by heart and exactly where lots of businesses and landmarks are. Most of all, it all feels easy. I’m not sure I even did this well when I moved to Owatonna five years ago, and that’s comparatively tiny and therefore a trivial problem set up against the whole Minneapolis–St. Paul metro area.

(I will grant that I think Minneapolis is an easy city to navigate in relative terms. I wouldn’t be doing so well if I had moved to a larger and messier city like, say, London or Tokyo. But I would still be doing better in London now than I would have done if I’d moved there five years ago.)

Since it seems like I’m doing something right, I thought I’d share some of the techniques I’ve figured out and been practicing recently. I’m going to focus on urban areas because that’s the problem I have my head down in right now and it’s likely the kind of area that people are most often thrown into suddenly and need to learn, but much of this could be applied to larger-scale rural areas (e.g., the main routes around a state you travel throughout for work) or even natural environments. I’m also going to assume that the city you’re trying to find your way around has its streets laid out in something that at least mostly resembles a grid; you’ll still learn plenty here if yours doesn’t, but some of my specific tips may be less applicable.

I will not assume you’re using any particular method of transportation. Some tips may apply primarily or only to driving, others only to public transit, others only to cycling or walking, but I’ll be equal opportunity (because I use all four myself). And while the title suggests this post is about “quickly learning a new place,” I’d venture these tips will be useful anytime you’d like to improve your navigation skills and intuitive understanding of an area, even if you’ve been living there for a long time but have never gotten to know it well, or you consider yourself bad with directions and navigation in general.

Why bother?

It might be worth taking a moment to consider why all this even matters. If you have a smartphone, like most people, you can get turn-by-turn directions to any destination at any time on your maps app and you don’t even have to think about where you’re going. I’ll be the first to say this is a useful capability, I love having it, and at times I use it even when I know where I’m going! (The app’s ability to understand traffic conditions and tell you how long it will take to get somewhere, as well as picking the shortest route under current conditions, is invaluable at times, as is its knowledge of up-to-the-minute public transit schedules. Google Maps can even tell me when my bus is running late.)

But I have a hard time feeling at home in a place unless I know where things are within it. And I feel a deep sense of satisfaction knowing exactly where I am or finding my way to a place I rarely go without looking at a map or taking any wrong turns. Maybe this isn’t a surprise – humans spent much of our time navigating around the landscape looking for food and other resources throughout our evolutionary history, so it makes sense that many of us would feel somewhat incompetent if we don’t know where we are and what’s around us.

Sure, you’ll eventually learn where most things are in your environment if you just follow the turn-by-turn directions enough times – but it can take a surprisingly long time. And even then, you’ll have learned only to repeat a specific set of paths. It will take even longer to start understanding alternative routes or where some of these places are compared to others – depending on your natural aptitude for this and how complicated your city is, maybe years! As my little experiment has shown, if you put a moderate amount of effort into it, it’s entirely possible to gain most of this knowledge at least for the places you spend the most time in a matter of weeks, even without any particular talent to speak of.

A side benefit is that navigating on your own initiative requires you to watch the world around you. When you’re following directions from your GPS, you can drive around without ever looking at anything except the road in front of you. Believe it or not, there’s a lot of valuable information out your window! You might discover your new favorite spot on your way to somewhere else, but only if you’re not looking at your phone the whole time.

Personally, I also think it’s fun to get to know a place by feeling my way around it and making a few mistakes. So much so that sometimes I’ll even do this on vacation rather than using my GPS, even though I’ll probably never be back and gaining a lasting understanding of the geography isn’t useful. But maybe I’m just weird.

General skills

In case you’ve never learned any of the skills you need to find your way around on your own, I’d recommend getting at least decent at two things before continuing with this article: using a map and intuitively understanding cardinal directions. (Some of my readers may think I’m being ridiculous by even including this section, but I know plenty of adults my age who have never learned how to use a map.)

As I’ll discuss later, watching for landmarks is a valuable supplement to the spatial reasoning tied up in these two skills, but if you want a full understanding of the layout of an area and the ability to quickly make up new routes on the fly, you’ll do much better if you can work in absolute space using a physical or mental map and cardinal directions. I recognize this is different and challenging for some people!

-

Using a map: Learn to understand all the information on a typical map and to navigate without using any computerized routing tools (e.g., the “Directions” button on your maps app). Find where you are on the map, find where you need to go, and translate the route between those points on the map into actions in real life.

If I were learning map skills now, I would be inclined to pick up a good paper map of the area and work primarily with that rather than a maps app – it’s much easier to learn to use a large map than a phone-screen-sized one, and you won’t be tempted to use directions or other electronic-only features. That said, the “you are here” blue dot is a huge convenience, and finding your current location on a paper map can be challenging if you don’t have much experience doing that, so if you’re struggling, you could consider starting with an electronic version and then working on learning the skill of finding your position on a map without such a dot separately later.

It’s totally fine to use computerized routing most of the time – I do it myself anytime the best route isn’t obvious – but you should make sure you can do it yourself effectively first. Not only is it a useful skill if your phone ever isn’t working properly or the route it picks is stupid or doesn’t match ground truth, I believe working with maps has the power to make you better at thinking about spatial relationships, and thus improve your overall navigational skills.

-

Using cardinal directions: There are two subskills here.

-

Quickly working out which direction you’re facing: Without this skill, it’s hard to use a map, including a mental map in your head. Three methods are particularly helpful in a typical urban environment: a compass (you probably have one on your phone and you might have one in your car; this is great as a backup or to check your work in an unfamiliar location), the position of the sun (to the east before noon, to the west after noon, and in the northern hemisphere angled a bit towards the south in the winter and the north in the summer, further near the solstices), and reference to another known point (if you know roughly where you are in the city and you can see an obvious natural feature that you know is to the north of your current position, or you know a fact about the streets like “street numbers increase from north to south” and you can see two street numbers).

Once you know an area well enough, finding your current direction with the reference-to-a-known-point method will be so trivial you might not even notice yourself doing it, but until then, it’s important to be able to work it out explicitly.

-

Knowing what cardinal direction things are relative to others: On the flip side, if you’re looking at some landmark and you want to go to some other place you’re familiar with, you want to be able to work out whether you need to head north, south, east, west, or somewhere in between to get there. Obviously, you can figure this out by looking directly at a map, but you want to work towards doing it entirely in your head by imagining a map or some kind of spatial representation.

-

Recommending ways to improve these skills is beyond my pay grade. Personally, I’d start by just doing them as much as possible, but that might be hard if you’re starting from zero, and it’s likely that others have come up with great tips and tutorials. Send me an email if you find anything particularly awesome and I can mention it here!

As you’re navigating

You can get started with these techniques immediately, and they take little or no time out of your day because you do them while you’re moving around the city, which you presumably need to do anyway. However, be aware that they’ll teach you more when you work on your Background Knowledge (second section of this post) first or simultaneously, because you’ll have more context to attach what you learn to.

Pay attention!

Many people never improve their navigation skills because they consider themselves bad at navigation and consequently always delegate navigation tasks to someone (or some app) that’s better. If you aren’t actively paying attention to where you’re going, you can easily travel the same route a dozen times without learning anything. So whenever you go somewhere in the area you’re trying to learn, either take responsibility for navigating yourself, or watch carefully where the navigator is going and test yourself as you go (see Make connections by quizzing yourself, below).

By always paying attention to where you’re going even if someone else is giving you a ride or you’re using turn-by-turn directions, you’ll learn much faster.

Make connections by quizzing yourself

As you travel, call out what landmarks you’re passing, where you need to turn next, and why you need to do that. Additionally, when your attention isn’t otherwise occupied, quiz yourself or have a travel companion who’s also interested in learning the area quiz you with questions that test your spatial awareness and knowledge of your surroundings. If you’re alone in a car or at sufficient distance from other people, or you’re with others who are in on the project, answer out loud – it’s easier.

You can make up any questions you think would be helpful, but here are some good ones to start with:

- What cardinal direction am I facing?

- Can I visualize roughly where I am on a map?

- What neighborhood am I in? What neighborhood am I going to? What neighborhoods are between them?

- What direction would I go to get home from here?

- Are there other destinations I’m familiar with near here? How would I get to them?

- What’s the next major road or highway exit I’m going to cross?

- What’s the next landmark I’ll see along this route?

- If I went past the next turn by mistake, how would I know?

- If I were using a different mode of transportation (say, biking rather than driving), would it still make sense to come this way, or would I prefer another route nearby?

- If this street were closed or there were an accident blocking traffic up ahead, how would I route myself around it?

- Where’s the closest public transit stop and where could I go if I got on there? (If currently riding, what could I do if I got off there?)

- If I wanted to stop right here, where would be the best place to park?

Some of these questions will be hard to answer if it’s your first time going to a particular place, or if you’re starting without much experience trying to answer such questions. That’s OK – just ask them again when you travel the route again, and as you learn more about the route and the city as a whole, they’ll get easier. If you get stumped by a question that seems like one you should be able to answer or would particularly like to be able to answer, take a few moments when you arrive or when you get home to look at the map and answer it (Google Maps’ Street View can come in handy for some of these questions, too). If you discover something particularly insightful, it’s also a great idea to make a flashcard with that information on it (something we’ll discuss further in the second part of this post, Gaining background knowledge).

By regularly asking these questions, you’ll find ways to relate the information you’re taking in as you travel to other places you already know. That’s the best thing you can do for your knowledge of the area, because the more connections you form with any idea, the better you’ll remember it. You’ll also just get better at answering these kinds of questions from whatever information you currently know, which is great because they’re legitimately useful questions when finding your way around! And asking or answering questions forces you to pay attention even if you aren’t the one navigating.

Be smart with turn-by-turn directions

Turn-by-turn directions can slow down your learning curve dramatically because they discourage you from paying attention. To have a route learned by heart, you need to be cued to make your maneuvers and identify your current position based on landmarks and street names, and to fully internalize the geography of an area, you need to understand where this new route is relative to other places you know. Turn-by-turn directions instead cue your turns primarily based on “the computer voice told me to turn right in 300 feet”, so the cues that you’re reinforcing by following the directions won’t be useful to you when the computer voice isn’t there any more. In other words, the knowledge you gain by following turn-by-turn directions isn’t transferable.

Of course, eventually you’ll probably start recognizing landmarks or streets simply because you’ve seen them a few times, and then you’ll be able to figure it out without the computer there, but this will happen only by accident and it will take a long time. We can do much better. (This is the same concept as active vs. passive recall in memory work: because you’re not actively using the information about the landmarks or streets, each repetition has a much smaller impact on your memory.)

There are two main ways you can avoid relying on these untransferable cues without giving up all the benefits of modern technology.

Best, just avoid turn-by-turn directions altogether. Importantly, I’m not saying not to click the “directions” button on your maps app to figure out how to get from place to place (unless you don’t have basic map skills yet). This is a great tool, especially if you don’t know the main routes well yet; it’ll pick out at least one sensible and fast route that you can use. But once you request a route, spend some time looking at the map and the turns required, memorize those, lock your phone, and drive/walk/ride to your destination without letting the app talk you through it. If you forget where you’re going or you get lost, stop and quickly look at the directions again.

This is certainly more annoying in the moment than listening to voice directions, but it forces you to pay attention to your surroundings to figure out where to turn, so you’ll learn much more. I can usually learn a route by heart the first time I use it when I do it this way (at least when I have the return trip to reinforce it), whereas it often takes me four or more repetitions with naïvely used turn-by-turn directions, and even then I usually only learn how to take that specific trip and don’t improve my overall knowledge of the area.

This approach is admittedly much easier in cities with a straightforward street network. When you need twelve turns to get to a destination, it’s a lot harder to memorize them! However, no matter what the city’s design is like, it gets easier the more you learn: once you know some basic routes for crisscrossing the city on main roads, you can chunk large portions of the directions into a single route, so even complex trips can be simply represented in your memory.

If you aren’t willing or able to avoid the directions completely, perhaps because you’re in a hurry or there are just too many steps to effectively memorize given your current knowledge, try using directions on the way out but making the return trip on your own. You have to plan ahead for this to work in most cases; if you just absentmindedly follow your phone’s voice directions on the way out, you’ll rarely have picked up enough details to figure out where you’re going on the way back. But if you know ahead of time that you’re going to ask yourself to find your own way back, you’ll probably pay much more attention to where you’re going, and this alone might be enough to teach you the route pretty well even when following the computer voice. For best results, quiz yourself on your trip out, focusing on questions about how to get home from your current location, what landmarks you see at turns, and how the streets you’re using relate to each other.

Both of these strategies require navigation to take up a much larger portion of your brain (and if you’re traveling with others, your conversation) as you drive, bike, or walk than you may be used to. You should also be prepared to take some wrong turns now and then; this is normal and expected and doesn’t mean you’re doing anything wrong (indeed, figuring out where you went wrong and how you can get back on track will help you learn). So it’s OK to switch back to brainless turn-by-turn directions if you’re frazzled or in a hurry or otherwise don’t have the capacity to deal with it on a particular trip, but don’t get into the habit of doing this all the time; some time spent learning about your area up-front will pay off big-time down the road.

If you insist on using turn-by-turn directions both ways, you can mitigate the negative effects by aggressively quizzing yourself as you follow the voice directions; the problem is not so much turn-by-turn directions per se but the fact that they encourage you not to pay attention to where you’re going.

Note: If you’re wondering why I consider turn-by-turn directions an issue at all if quizzing yourself solves it and I already suggested quizzing yourself on whatever trips you take: I find I usually don’t have the willpower to quiz myself extensively enough in this case. When a machine is telling me exactly where to go, I seem to just switch off my brain and start daydreaming instead. I suspect others are similar.

Use landmarks effectively

Landmarks have a useful role to play in finding your way around – they make it easier to notice locations where you need to take some action in visually complicated environments, they provide reassurance that you’re going the right way, and they serve as useful anchor points in your mental map of the city. But for people who are naturally particularly landmark-oriented, particularly people who remember most of their routes by memorizing reactions to particular landmarks (e.g., turn right at X), they can also become a crutch that prevents fully understanding the geography.

Studies have suggested that knowing where the streets are, in a map-like mental representation, yields better functional results in a variety of navigation tasks, so this doesn’t seem to be just my own bias speaking here. When you use landmarks to navigate a particular route without understanding where the landmarks are located, you usually won’t be able to draw on either those landmarks or the street layout to navigate to a place you’ve never been before, except perhaps by reusing part of a route you already know.

Here’s how to get much more out of landmarks: rather than just learning what response you should have to them when traveling a particular route, also learn where the landmarks themselves are located in absolute space. If your city uses a street grid, this is particularly easy – just remember what two cross-streets the landmark is closest to (see the “Nearest-corner method” for memorizing locations). So rather than learning that you have to turn right at the McDonald’s to get to the grocery store, learn that the McDonald’s is at 25th Street and Oak Avenue. If you want, you can then also learn that you turn right at the McDonald’s when coming up Oak Avenue to the grocery store (either intentionally or by doing it enough times you remember it automatically). Now those two facts will let you trivially derive other facts that can help you with other navigation tasks, like:

- When you see the McDonald’s, you’re at 25th Street and Oak Avenue.

- If you want to go to McDonald’s (or someplace it’s on the way to) and you’re currently at 22nd Street and Oak Avenue, an intersection you’ve never been at before, you go south three blocks (assuming the street numbers are sane!).

- On the way to the grocery store from your house, you turn east on 25th Street.

It’s particularly helpful to use landmarks in this dual role when giving someone else directions: if you tell them what street to turn on, then also say a particular building is on that corner, they’ll be much more likely to spot at least one of the cues at the right time. It’ll be up to them to store the most useful cognitive representation for future trips!

I have no scientific basis for this, but here’s one more suggestion. I am generally not a landmark-oriented person, but I find myself relying on landmarks, and specifically the use of landmarks whose absolute location I don’t know, much more heavily in areas that are otherwise unfamiliar to me (for instance, vacation spots). I think this is because I have no idea where the streets are in relationship to each other, nor do I have a good overall picture of the area, so I would be reduced to memorizing a sequence of unfamiliar street names to follow the route, which is more difficult than memorizing a sequence of visually salient places. I therefore hypothesize that you can lessen your dependency on landmarks and thereby increase your navigational versatility by simply spending more time looking at the map and getting a better overview of the area – something we’ll discuss shortly in the “Background knowledge” section.

Switch up your modes of transportation

The world looks different depending on whether you’re driving, walking, riding a bike, or taking public transportation. So it’s worth trying out all of the modes that are practical for each trip. The more different ways you see an area, the faster you’ll learn the ground truth of what it looks like and how it’s laid out, rather than simply the distorted view you get from the seat of a particular kind of vehicle.

Take a wider variety of trips

Consider this technique optional, but if you have an excess of motivation to put towards the project of learning your area and you want to speed up the process, this may be a good place to direct it.

When you get familiar enough with a route that you can always answer your quiz questions easily, consider extending your learning further by picking an alternative route and learning that one the same way. This won’t always be practical, particularly when using public transit, but sometimes it can be. (There will often be dozens of practical routes when walking within a street grid, so that’s a great reason to walk more!) Using multiple routes may also teach you useful information about traffic patterns or allow you to explore a new area you didn’t know about.

You can also intentionally add extra trips and trips to different places into your everyday life. For instance, you might choose to run to the store to buy something that you would ordinarily buy on the web, or purposefully not combine errands, or go to a less convenient location of the same business. I’ve even heard of people working Uber Eats or Instacart for a few hours a week to get exposure to a bunch of different random destinations they wouldn’t ordinarily go to.

Gaining background knowledge

The strategies for while you’re navigating are the easiest to apply, since you can use them as you’re traveling around the city, which you already had to do anyway. But if they’re all you do, you’ll be spending all your time zoomed in on individual trees; for best results, it’s helpful to do some book work as well so you can get a look at the whole forest. This doesn’t have to take a lot of time, and it can be a fun part of educating yourself on your new place.

Background-knowledge strategies fall into two main categories: learning the overall lay of the land so you have something to anchor what you learn on your individual trips to, and memorizing individual facts you’ve learned on your trips for future reference. Both are aided immensely by a good spaced repetition system – and if you don’t use one, check out the link – but you should still be able to apply them without one, it just won’t be as easy or effective. Whether using spaced repetition or not, create flashcards for the most important things you learn in the sections below and study them regularly. If you don’t already have a serious flashcard routine, this might sound pretty nerdy, but it will absolutely work, and it’s not difficult.

Look at the map as much as possible

Knowing an area really well is often described as “having the map in your head,” so it stands to reason that the more time you spend (smartly and purposefully) looking at a map of the area you want to learn, the better.

When you first realize you need to get to know an area, spend as much time as you can stand exploring the area from a distance via Google Maps (on the largest screen you have) or a high-quality paper map. Look for points of interest like neighborhoods, business districts, parks, major roads, and so on, and spend a while studying how the streets connect these places. You don’t need to explicitly try to memorize anything, but whatever basics you retain from this exercise will give you a scaffold to attach the new facts you learn to as you continue to learn about and explore the area.

Going forward, every time you’re going to go somewhere and don’t know where you’re going, study the map and try to connect the new place to any nearby places you already know or routes you’ve used before. Even if you’re going to be using turn-by-turn directions, look at the route on the map before you use them. See if you can select the place you need directions to, or at least find its general neighborhood, by scrolling to it on the map instead of using the search function. If you get lost or confused while you’re out in the city, find that area on the map later (or better yet, immediately on your phone, if you aren’t driving) and see if you can figure out where you went wrong.

Learn the most important features via flashcards

To solidify the understanding of the overarching city layout you get from looking at the map, focus on explicitly memorizing four things: counties, neighborhoods, major roads, and streets.

-

Counties: If there’s more than one county in the area, learn what they’re called and roughly where they are in relation to each other. This isn’t all that important, but there also won’t be many of them, so it takes little effort and will undoubtedly come in handy from time to time; counties often come up on the news, in government publications, and on highway signs.

-

Neighborhoods: Learn what the locals call each area. This will allow you to intelligently discuss places in the city with others and quickly understand the locations described by signage and business websites, but even more importantly, it gives you a clear way to think about the city. It’s much easier to understand where you are and remind yourself where you’re trying to go when you can give names to the places you see. Street names are helpful, but sometimes they’re too detailed.

“Neighborhoods” should include nearby suburbs and towns you might go to, talk about, or use to orient yourself on the highway, if your area has them.

Be aware that in many cities, small neighborhoods are often grouped together and given overarching area names, so try to learn these as well as the names of individual neighborhoods (and start with the large groupings if you have limited time, since those tend to get the most use and are most embarrassing if you haven’t heard of one).

-

Major roads: Learn the names and locations of numbered highways, arterial roads, and the like. These often have more than one name; the name might change from place to place, or there might be a street name as well as a number and an unofficial nickname. Try to catch all the names.

Most obviously, knowing major roads is helpful because you’ll often want to travel along them when driving or taking public transit. They’re also incredibly useful for orienting yourself; if you know where all the major roads go, when you cross one of them or see it in the distance, you’ll have a good idea of where you are within the city on at least one axis. And while this is less relevant now that most people have GPS, if you ever get lost, you only need to continue until you find a major road and follow it to a cross-street you know, and you’ll know exactly where you are.

-

Streets: It’s usually impractical to learn the names and layout of all the streets in even a medium-sized city, but for areas you live, work, or spend a lot of time in, it’s likely worth learning all of the street names within a radius of a few blocks. This serves several purposes:

- You’ll have an easier time memorizing where nearby landmarks and businesses are, once you find them.

- If you want to go out for a short walk, you can wander down random streets and still always know how far away you are and how to get back.

- If someone is coming to meet you and gets lost nearby, or someone on the street stops you and asks you where something is, you’ll be able to give them useful directions.

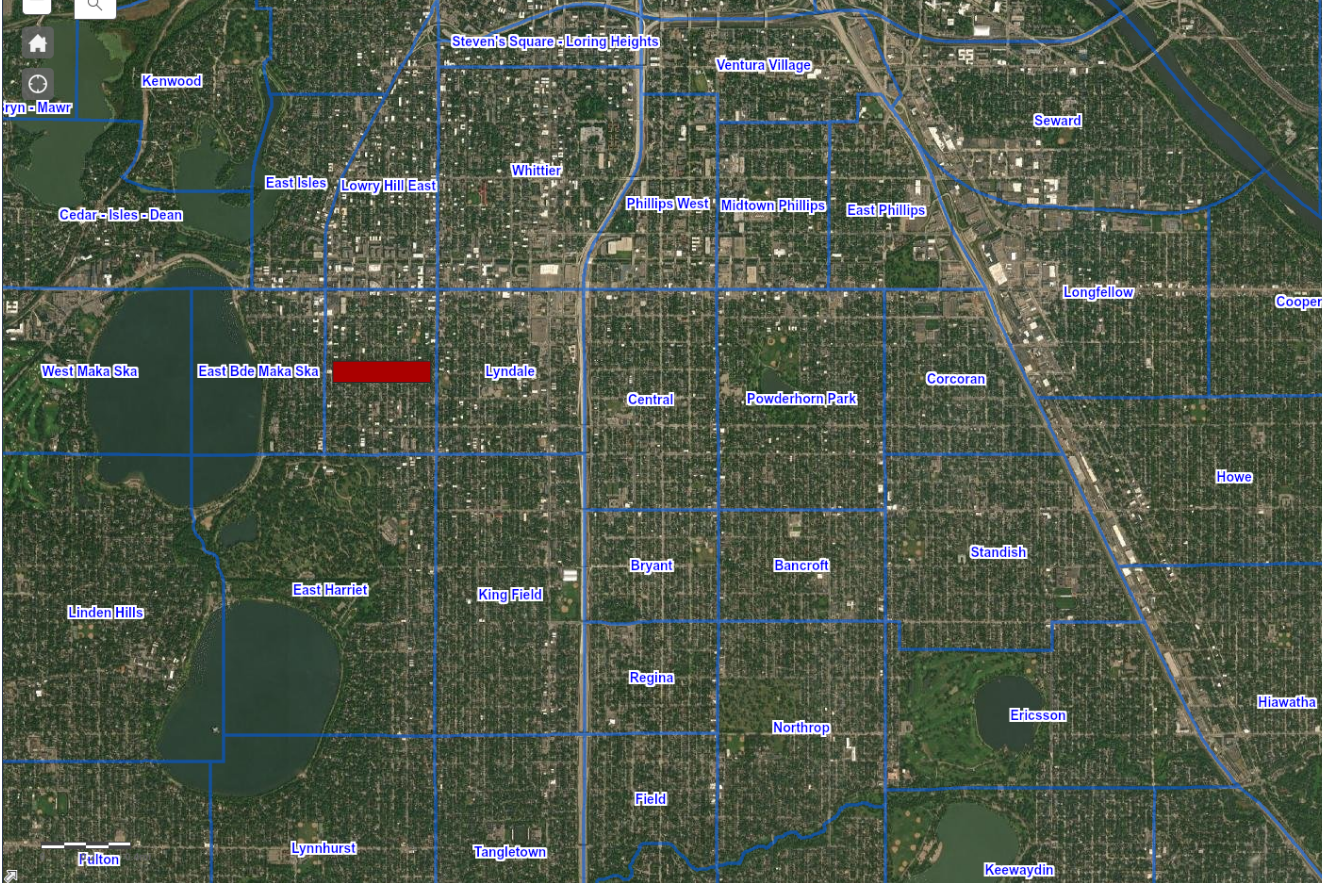

Now I can hear you saying, OK, this sounds great, but how do I learn all of this? Before my last move, I assumed this was the kind of familiarity that you can only get after several years of living in an area. But then I realized there’s a simple learning technique that you can use to cram all this into your head on whatever time scale you want, with minimal initial investment: image occlusion. Image occlusion means taking an image, hiding (occluding) a small portion of it, and asking yourself to fill in the blank. In this case, we take a map or diagram of the area we want to learn about (you can find any map you fancy on the web and download or grab a screenshot of it) and block out the street names, or highway numbers, or neighborhood names. The map with the occluded bit goes on the front of a flashcard, and a full version goes on the back. Here’s an example showing the official neighborhood names in my area of Minneapolis (occluded is South Uptown):

For Anki, you can use Image Occlusion Enhanced to create image occlusion cards. Once you have the add-on installed, you just paste or browse to your map and use the supplied editor to draw boxes over the items you want to obscure, then click the add button and voilà, you have flashcards.

Learn how streets work

Cities, being designed by people, have some underlying order to their layout. Cities that were centrally planned in whole or in part or whose streets have a fairly strict grid layout have more order than natural ones, but even the most beautiful messes usually have some tricks you can learn. However, these points of order may not be obvious from just moving around the city unless you’re paying careful attention, so it’s helpful to do some research.

Here are a few things to check out in particular:

-

How long are the blocks? If it’s a regular amount, say an eighth of a mile, you can use this to estimate the length of a route in your head (and, eventually, the travel time, once you get a feel for how traffic normally flows on major roads). It will also help you feel whether you’ve gone the right distance; if you know from looking at directions that you need to go a mile, you know that’s about 8 blocks.

Some cities have different block lengths in different directions; for instance, most of Minneapolis has blocks that are an eighth of a mile long north to south and a sixteenth of a mile long west to east. This is a handy cue for orientation, since the “grain” of the streets feels noticeably different in one direction compared to the other. Similarly, block lengths may be different in some areas of the city than others, which can help provide reassurance that you’re in the right place or alert you that you’ve crossed into a different neighborhood.

You can spot most of these differences on Google Maps, and a quick web search can answer any questions that remain.

Tip: If you right-click anywhere on Google Maps, there’s an option to measure the straight-line distance between two points.

-

Are there any patterns to how streets are named? Many cities with grid layouts have “Streets” running in one direction and “Avenues” in another (most commonly west-east and north-south, respectively). Streets that don’t follow the grid pattern might be called “roads” or “lanes” or “parkways” or something to that effect. Figure out whether there are any such standards in your city.

Some sets of streets may use sequential numbers or letters or other kinds of sequences. These make it much easier to figure out where you are and where you’re going – but only if you notice there’s a pattern and figure out how it works.

Oftentimes a pattern will be interrupted by major roads; the interrupter might either replace a number/item in the sequence or get slipped in between two of them. Either way, learn where it fits.

Some cities use different colors or symbols on their street signs to add additional information (for instance, Minneapolis indicates which streets get plowed first in a big snow, and thus where you shouldn’t park in such conditions, with blue signs). This is comparatively rare, but it’s worth checking for.

-

Is there any pattern to which streets are one-way? There’s nothing more annoying than driving up to your destination when you’re running late, only to discover that the last block is one-way the other way and you have to go all the way around the block (which, due to Murphy’s Law, will inevitably be filled with unusually heavy traffic). If your city offers some way to determine where the one-ways are without memorizing them one by one (say, even streets in one part of town go one way and odds go the other), learn that.

-

How does the address numbering work? Most cities (at least in the US) use some form of a system where all addresses are split into North, South, East, or West by two perpendicular “center” streets, and numbers start from the 0 or 100 block from there. What streets do the division? If the city has numbered or lettered streets in one direction or another, do those numbers line up with the address numbers, and if so, how? (In Minneapolis, for example, between 26th Street and 27th Street, all addresses are 2600-something.) Or does your city do something odder with the numbers that you should be aware of?

Once you master the address numbering, you can often get a solid idea of where a building is purely from looking at the street address, even if you’ve never been anywhere near the destination before. I know plenty of people who live in one place their entire life and still treat street address numbers as essentially random!

One trick for mastery if you want to take this to the next level: in directions whose streets aren’t numbered, memorize the offsets of a few major streets. Say you see an address of 3205 23rd Street E and you want to know roughly where this is in the east-west direction, which in this hypothetical city doesn’t exhibit any naming convention. It’s impractical to count off 32 streets from the center street to figure this out – even if you actually know what all of them are, which would be impressive on its own – but if you know that Washington Avenue is the start of the 3000 block on the east side of the centerline, you can instantly pinpoint the building in your head as three blocks east of Washington Avenue on 23rd Street.

Learn miscellaneous geography

-

Are there any noticeable natural features? Many cities have significant hills, rivers, lakes, distant mountains or oceans, or other features visible from some parts of the city. If these are conspicuous, they can be helpful for navigation, either by indicating a cardinal direction or by dividing neighborhoods, so learn where they are.

-

Are there any boundaries where most streets don’t go through? Which ones do? Oftentimes cities cross natural barriers like rivers or ridges, or artificial ones like railroad rights-of-way, which may mean that most streets dead-end in that area. If there are a small handful that go through, note which ones those are so you know to get on one of those when you need to cross the barrier.

Memorize locations

You can rapidly learn and permanently retain the locations of businesses, residences, landmarks, and other spots you encounter by making flashcards asking where they are. This may in fact be my favorite tip of everything I’ve mentioned in this post. Don’t, however, write the street address on the back of these cards. Although this is an obvious way to indicate the location of a particular place within a city, it’s challenging to remember and not that easy to navigate to unless you’ve already become a wizard with street addresses in your city. I use one of two alternative methods instead:

-

Nearest-corner method. Record the two intersecting streets nearest the location. If you can’t physically see the location when you come up to that corner, additionally include a simple cue that will get you from the corner to the location, using either cardinal directions (“continue north from northeast corner”) or a landmark that is visible right away (“behind the gas station”). I tend to find the landmark more memorable if there’s a good one, but sometimes there isn’t anything particularly eye-catching in the right place.

If there is a strong grid layout and you know the streets in the area reasonably well, this is by far the best way to memorize a location. It’s both easy to remember and easy to interpret, regardless of where you are in the city at the time you need to navigate there.

-

Route method. From a known location (good choices include your home, a highway exit that you know how to get to from anywhere in the city, or another nearby place that you know well), indicate the streets you need to turn on to get to the destination and, if there might be any doubt, which direction you turn. At least in a grid layout, there will typically be only a couple of turns, so this is still reasonably easy to memorize.

This method is appropriate when you don’t know the surrounding area well enough to confidently navigate to the nearest corner. The knowledge is less transferable, but you can still adapt it if you have a different starting location by getting yourself to some point in the middle of the route, so it’s not too bad. Nevertheless, if you get to know the area better, it’s worth considering changing the card to use the nearest-corner method.

In either case, if you’re likely to drive to the location and the best parking location isn’t obvious, or you’re likely to take public transit and the line and stop isn’t obvious, it’s helpful to also record that information on a separate flashcard.

How to get started

I hope this post gave you some good ideas, but it may be a bit overwhelming – I included a lot of different things you could work on, and you can’t do them all at once. One of the common flaws of posts like this is that they don’t provide any obvious next actions, so most readers go, “Huh, interesting,” close the tab, and never do anything as a result. To try to combat this, here are some easy steps you can apply in order – but feel free to adjust depending on what ideas you find the most intriguing or personally applicable.

- If you need to work on anything in the General Skills section, consider doing that first. But if this sounds difficult and you think there’s a risk it will prevent you from getting started, skip this step (and any following steps you find your lack of these skills prevent you from taking effectively) and come back to it later.

- Spend some time – maybe half an hour to two hours – studying the map, if you haven’t done so already.

- Get in the habit of always paying attention to where you’re going. When you don’t know where you’re going and are using a maps app, use one of the strategies for reducing the negative impact of turn-by-turn directions.

- Learn details of how the streets work and any major natural features.

- Start quizzing yourself as you travel. If you have trouble remembering to do this, try asking one question every time you stop at a red light.

- Every time you go to a new place you might conceivably want to return to, make a flashcard for its location. Do the same for landmarks you encounter. If you have trouble remembering to do this, try doing it immediately after looking up the directions to a place (you might be able to make a slightly better card with more information after you’ve been there, but having a mediocre card is better than having no card – you can always improve it later).

- Review your flashcards regularly. Find a time in your daily routine for this activity so you don’t forget. More on this in When to Learn With Anki.

- Once you get used to reviewing the flashcards (if you don’t already have an appropriate routine), create and mix in flashcards for important features.

- If you still want to do more, consider switching up modes of transportation or taking a wider variety of trips.

Note: If you haven’t yet moved to the new place you’re trying to learn, skip steps 3 and 5 and come back to them once you’re on the ground.

Have fun! And if you find this helpful, please consider sending me an email to let me know what did and did not work for you – while I’ve presented this as a method, it’s more of a collection of things I’ve noticed seem to help me, and I’m only making educated guesses about whether they’ll work for other people.